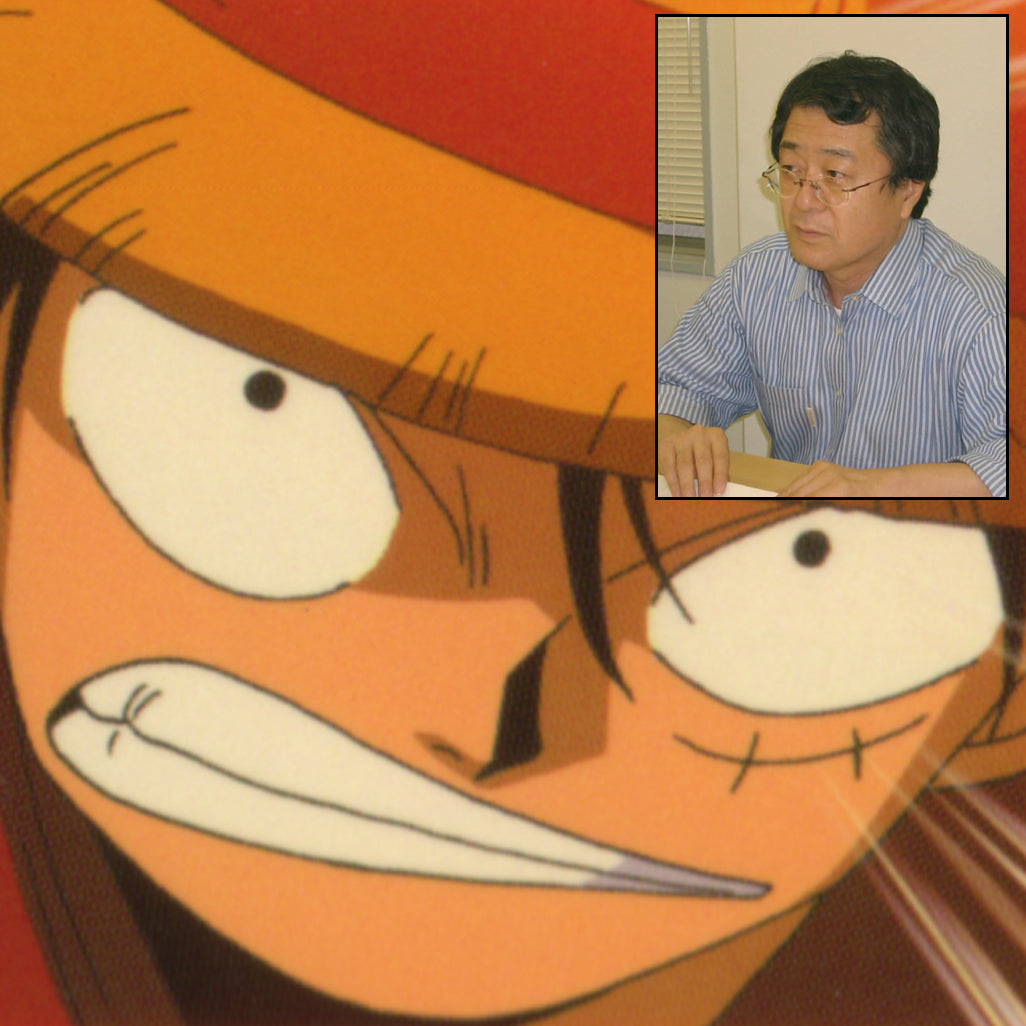

An interview with One Piece producer Shinji Shimizu

Posted by Glenn Kardy on

In Japan, the name Toei is synonymous with animation, and it is Shinji Shimizu's duty to ensure the studio continues to live up to its strong reputation.With the overwhelming popularity of his latest series, "One Piece," Shimizu proves he is the right man for the job.

This interview was conducted by Manga University founder Glenn Kardy in April 2004.

MANGA UNIVERSITY: What exactly does a producer do?

SHINJI SHIMIZU: There are so many animated programs on the air in Japan, more than 60 every week. And they’re on all the time—prime time, early mornings, late at night. For me and everyone else in the business, prime time is where you want to be. But there are so many

factors you have to take into consideration when you have a show on in prime time, like sponsors, broadcasting rights and the tremendous amount of money involved. It’s up to the producer to find not only a good program, but the proper time at which to air it.

For example, if you put a children’s cartoon on after midnight, no one will watch it. So first you need to identify your target audience and when they’re likely to be watching television, then do your best to get the piece on in that time slot. Then, once your show is on television, you need to consider the tie-in merchandise. It takes six months for toys and other products to reach the shelves, and a year for a game to reach the market. So no matter how good your anime is, if it’s canceled in less than six months it won’t sell any merchandise because the products aren’t even in stores yet. You’ve got to do your best to keep the show on the air long enough to sell your merchandise.

MU: Do you work closely with the toy companies and retailers?

SHIMIZU: Yes, of course. We have to select which characters are best suited to become toys or action figures. We have meeting after meeting with manufacturers and other professionals. Of course, creating something fun that also sells well would be best for everyone, but it doesn’t always work out that way. Children are very sensitive to these things, and can sense when a cartoon has been created just to sell merchandise. They know. It’s amazing. So you have to have very good techniques to make sure that kids don’t feel like you’re just trying to sell them something.

MU: What happens if the animation is popular but the merchandise is not?

SHIMIZU: That happens a lot. For example, I was the producer of “Kindaichi Shonen no Jikenbo” (The Case Files of Young Kindaichi). That was on the air for three and a half years, prime time, Mondays at 7 p.m. We lost a lot of money and the merchandise didn’t sell, but the TV ratings were good.

MU: Although it was popular with audiences. did you consider it a failure because the merchandise failed to sell?

SHIMIZU: No, because usually if a program doesn’t work out, the network will pull it off the air in six months or a year. But because that particular program was popular and stayed on the air for three and a half years, the network was grateful to us. But my company was angry, and told me to get back the money we lost on the show. (Laughs) Fortunately, “One Piece” has made a lot of money, much more than we lost on “Kindaichi.”

MU: So one program helped cover the loss of the other?

SHIMIZU: Well, it did In my mind. My company is still mad (about “Kindaichi”), though. (Laughs) But I’d always wanted to do a mystery and “Kindaichi” came up, so I jumped at the opportunity. As a producer, I was very proud of my work, and it wasn’t just for kids. Adults enjoyed that program as well. That was the type of animation that I had always wanted to do.

MU: When you’re developing new programs, are you on the lookout for fresh, undiscovered talent?

SHIMIZU: Of course. We make cartoons for children, but there are many manga written for all ages. There are comics for infants, schoolchildren, even adults. For my productions, I tend to look in magazines for boys, such as “Shonen Jump,” “Weekly Shone Magazine” and “Shonen Sunday,” as well as other mainstream manga weeklies.

MU: And that’s where you get ideas for new cartoons?

SHIMIZU: Well, I want to. But of course every producer in Japan is thinking the same thing. So getting the rights to animate the most popular manga in “Jump” is a load of work. For example, “Kindaichi” was the number one series in “Weekly Shonen Magazine.” “One Piece” was the top piece in “Jump.” So it’s up to the producer to use all his skill to get comics like these animated for his company.

But I don’t take the artists out and wine and dine them in Roppongi (an exclusive area of Tokyo). I don't pamper them. That’s not my style. I believe the best work comes when we can all get along as we complete a project. That’s the best way to do business. Of course there is a technique to this, but I don’t think there’s anything special that you can do. They just come to me.

MU: So when you are able to land a big artist or series, they are going with the reputation and quality of Toei?

SHIMIZU: Yes, yes, of course. Toei is the largest company, and I do have a reputation with all the other work that I have done in the past, so they do come to us. It is sometimes better to wait rather than to keep pestering them. It’s not because I’m great or anything, though! (Laughs)

MU: But still you have to persuade them because, for instance, Eiichiro Oda, the creator of “One Piece,” probably had other options. You had to convince him to go with Toei.

SHIMIZU: Yes, it is a lot of work. There are a lot of great people surrounding a great piece like that. And everyone is very proud, so we have to push our way through.

MU: Has there ever been “the one that got away”?

SHIMIZU: It’s all about the ones that got away. But most of them failed because they didn’t come to me. That’s how I look at it. (Laughs)

MU: But there’s enough manga in Japan for all the production companies to stay in business, right?

SHIMIZU: Well, young children aren’t reading manga anymore. Children’s books and magazines now contain more information than manga. So “Shonen Jump,” “Weekly Shonen Magazine,” “Shonen Sunday” and other publications that once targeted elementary school kids are now going after older audiences. They’re targeting junior high and high school kids. The problem with that is there are fewer good pieces that we can turn into cartoons for younger children, which is Toei’s target audience.

MU: In North America, there is a huge back catalog of Japanese animation coming in, so the market is flooded. In Japan, do you see a trend where there is less and less available?

SHIMIZU: It’s gradual. Maybe over the past 10, 15 years, older people are reading more manga and they want a better story. So to satisfy these readers, the stories are getting more complicated, and that means they’re also more difficult for smaller children to understand. Older readers also want more action and other adult situations, so there is more violence and more sex. “One Piece” is an old-fashioned pirate story. The characters want to fight with their hands, not guns. Children want to see this kind of anime.

MU: Then, “One Piece” is a return to a more traditional type of anime?

SHIMIZU: Yes. And because of “One Piece,” similar stories have been made or are being made. Overall, the average age of manga readers is going up. But we are still creating cartoons for smaller children.

MU: Which audience brings in the most money?

SHIMIZU: Children from age 5 to around junior high school. Between ages 5 and 10, they buy toys and other products based on their favorite cartoon characters. From around 10 to 15 years old, they play games and buy music CD’s, DVDs, and such. Of course, this is not a perfectly accurate account, but I think this is close to the overall breakdown.

MU: So the older audiences are not buying the tie-in products?

SHIMIZU: I think they want to buy it, but after buying stuff like stationery, if they want more they buy games. Younger kids are happy with just a keychain on their bags, but when you get into junior high, you don’t want to put a keychain on your bag. Instead, you get closer to the story by playing a game based on the series.

MU: “Dragon Ball,” which was produced by Toei, has lasted well beyond its expected life span. What are your thoughts on that, and how do you explain it?

SHIMIZU: It’s hard to say. Of course, while they are making it, all their energy and efforts were focused on creating the work. Once it started getting popular, you begin to understand, you start realize why. I believe “Dragon Ball Z” is so popular now because of the games that were based upon the story. “Dragon Ball” ended about 10 years ago. A few years ago, we tried to revive it here in Japan, but it wasn’t very successful.

MU: If a popular series here doesn’t have the same success overseas, is it considered a failure? In other words, does the Japanese animation industry view overseas success as critical to overall success?

SHIMIZU: We don’t really think of success in both places while we’re creating something. We think first and foremost about success in Japan. Overseas success just tags along once the product is done. Of course, they do think of the overall marketing strategy in the beginning, but if it’s not popular in Japan, it won’t be popular anywhere else, either. This is our basic way of thinking.

MU: So when planning a series, you are only thinking about success in Japan?

SHIMIZU: Well, we do think about global success. But first, we have to believe in our product and believe that it is the best thing ever to come out. We have to be proud of our work. But we need to focus on getting the job done. There may be plans for an overseas market, but we can't think that far ahead in the beginning.

MU: How surprising was the success of “Dragon Ball” and “Sailor Moon,” and what did the company learn from those successes that can be applied to current productions to make them popular overseas?

SHIMIZU: First, we were not that surprised. Japanese animation has been aired in Europe for more than 30 years now. Italy, France, Germany, Spain. Many of these people have grown up watching Japanese anime. But Japanese anime was not too popular in the United States until recently. They did release “Sailor Moon,” “Dragon Ball” and “Dragon Ball Z” in the U.S. about 10 or 15 years ago, but they didn't do too well. But now, they’ve become very popular. We really wanted to break into the U.S. market, so we thought, this is it—our time has come. So now, we really have to consider the U.S. market and map out a good plan.

MU: Why do you think the United States was so slow to embrace Japanese animation?

SHIMIZU: It’s obvious. In the U.S., they have Disney. And this is something that I’ve felt strongly when I visited the U.S., but there are only two genres there: animation for children, and animation for adults. They don’t seem to have cartoons for teenagers. Adults in the United States control their children very well and they tell their children that you have to take responsibility for your actions. In Japan, if you go to Shibuya or Harajuku (commercial districts of Tokyo that are popular with young people), you’ll see elementary and junior high kids sitting on the streets, just hanging around. These are the kinds of children targeted by Japanese animation. But this in-between market doesn’t seem to exist in America.

But American pop culture does seem to be changing. Americans consider Japanese anime to be refreshing. I met some kids when I went to UCLA last year. They didn’t say much at first, but once they warmed up, I felt that they were seeking and feeling some of the same things as their contemporaries in Japan. Let’s face it: being a young person in today’s world is no bed of roses. You hear about sex, violence and crime day in and day out, and Japanese animation is sometimes known for its depictions of sex and violence. But the reality is, we don’t show much of that during prime time. Japanese children can select what they want to watch.

It seems like only the edgiest Japanese anime is aired in the United States, so their impression of our cartoons is based on that. The cartoons that most people in Japan watch—some of our best work—have not yet aired in the United States

Let me give you an example. At UCLA, I asked the students to raise their hands when I said the name of an anime that they’ve heard of. Let’s say there were about 50 people there. I mentioned “Sazae-san,” which is perhaps the most well-known manga in all of Japan. Only one or two people raised their hands. “Doraemon” (also incredibly popular in Japan) had about five hands. “Doraemon” is published by Shogakukan and is aired by the same company that publishes “Pokemon.” No matter how you look at it, “Doraemon” is much more interesting than “Pokemon.” “Pokemon” is game-oriented, which is probably why it’s so popular, but “Doraemon” has generated about 20 feature-length movies. And “One Piece” hasn’t aired over there yet, either.

Business aside, I personally want to make sure that the right message is conveyed by our cartoons overseas because I do believe that this is the best way to introduce Japanese culture. So if the kids take a liking to Japanese anime, they might have a fondness for the Japanese people. So through anime, I want people from all over to understand Japan and its people and the culture. Of course, I do think of business as well. (Laughs)

MU: Of all the cartoons you’ve worked on, of which are you the most proud?

SHIMIZU: I really like “One Piece” a lot. I also like “Ge-Ge-Ge no Kitaro.” The dream that I have now is to take “One Piece” all over the world. Since it's a pirate story, I think it would be easy to comprehend. The story behind “One Piece” could take place in any country. I’d like to do the same for “Kitaro,” even though it’s a very different story, very Japanese.

“Kitaro” depicts a very classical Japanese world, and could be difficult for overseas audiences to understand. So I’ve created a short animated promo for “Kitaro,” and it received an award for computer-generated artwork. I created it for PR purposes using all computer graphics, and I purposely made it in English. I still can’t believe that an interesting story like this hasn’t been released worldwide.

MU: The promo indicates “Ge-Ge-Ge no Kitaro” is “coming soon.” Does that mean we’ll soon get to see it in North America?

SHIMIZU: I sure hope so! The story is done. There are people who are interested, and I think it will be quite easy to find sponsors.

MU: And “One Piece?”

SHIMIZU: Many TV companies are interested. We just have to fine tune it, get rid of the cigarette-smoking characters (which wouldn’t play well in the U.S.!), some of the violence, etc. It’s already out in Europe. But “One Piece” is a bit difficult because the characters go through a lot, mentally. As a producer, I am very confident in its success, but it still might be difficult since there is a lot of eastern philosophy in it.

MU: What do you think the future holds for the Japanese animation industry in general and your company in particular?

SHIMIZU: We really want children all over the world to watch our shows, so we want nothing more than to spread the popularity of anime and sell our toys and other products. But this isn’t just about money. We can’t help every child living in poverty or a war zone. But if they can find the strength to live by watching our cartoons, nothing would make us happier. Just like “One Piece,” they can look upon the stars and find the strength to go on.

This interview is one in a series conducted by Glenn Kardy for the Tokyo Foundation's "Super Cool" manga-and-anime project. In 2004, the foundation embarked on an ambitious plan to involve universities, high schools, arts programs, community groups and media throughout the world in the study and analysis of Japanese manga and anime. Glenn Kardy, a longtime journalist, is the president and CEO of Japanime Publishing in Kawaguchi City, Japan.